Fred Morgan on Original Recorders

Imagine recording an album featuring a collection of original baroque recorders and having renowned recorder maker Fred Morgan (1940–1999) write the liner notes. In 1976, celebrated recorder player Frans Brüggen (1932–2014) did just that.

Brüggen first released his classic LP 17 Blockflöten in 1972.1 The triple album documents the sound of seventeen original recorders, including instruments made by some of the best eighteenth-century makers such as Bressan, Denner, Rottenburgh, and Stanesby. The selection includes instruments made by Dutch masters like Beukers, Haka, van Aardenberg, van Heerde, and Wijne, all played excellently by Brüggen.

Brüggen was responsible for writing the liner notes for the original 1972 release. His essay discusses the unique nature of the project, the instruments used, and reflects on the characteristics of the recorder:

If I have learned anything while making these recordings it must be what I have always suspected: the recorder is a beautiful instrument. But, also, that it can only be beautiful if really well made (if not, it borders on the category of mere whistles & toys) and very well played.

Brüggen’s comment clearly reflects his high standards. Although the 1972 notes extensively quote an essay by Dutch recorder maker Hans Coolsma, the liner notes of the 1976 re-edition, now in the form of a two-volume LP, feature two interesting essays by recorder maker Fred Morgan. As this is a vintage LP from the 1970s that is no longer in print and has never been released on CD, I found it worthwhile to rescue Morgan’s texts. Morgan possessed extensive knowledge of these invaluable instruments, and his remarks are full of sharp observations about them.

Fred Morgan on Dutch Baroque Recorders

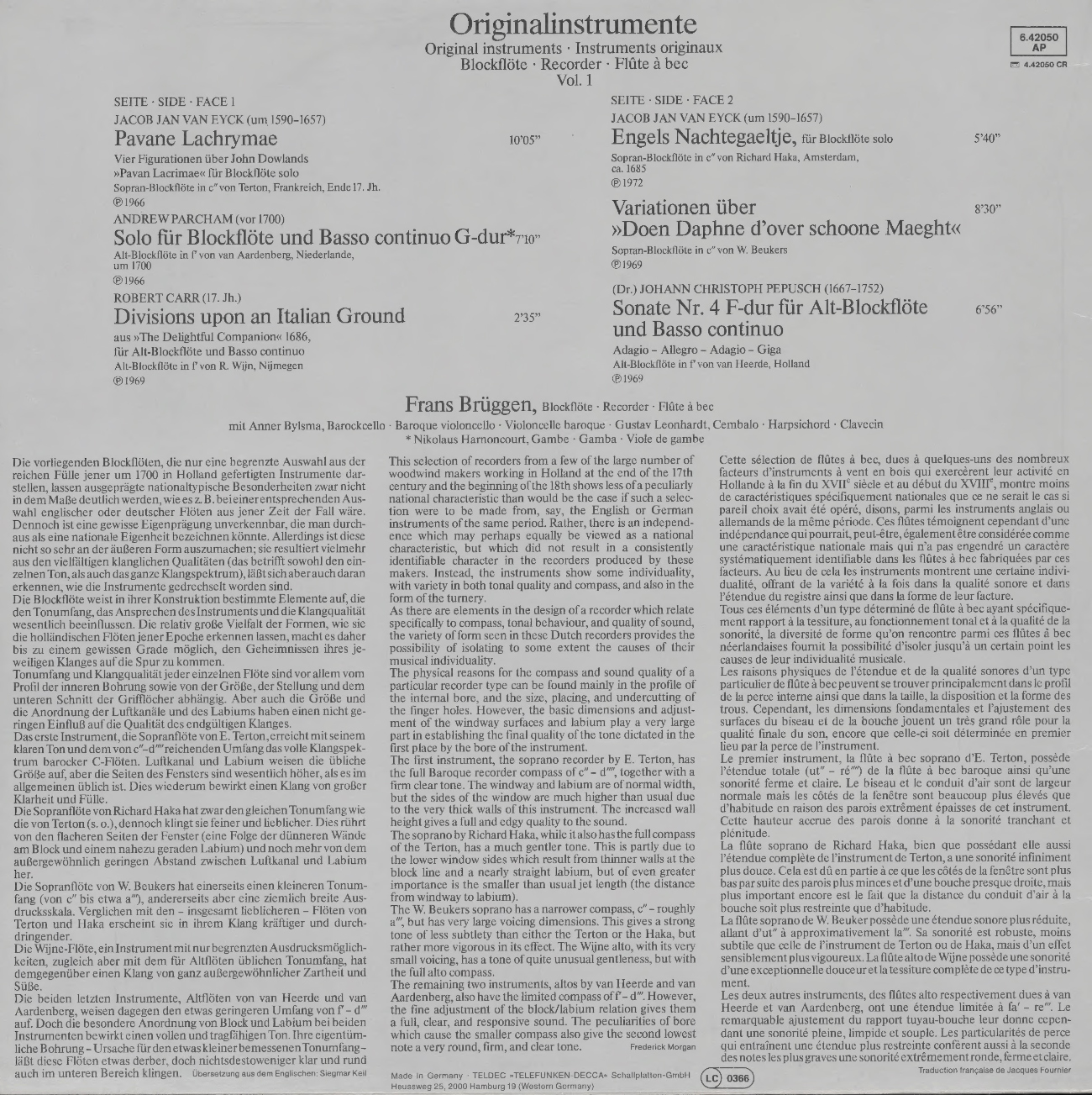

These are the liner notes for Vol. 1. In the first essay, Morgan discusses a selection of Dutch recorders featured in the first LP:2

This selection of recorders from a few of the large number of woodwind makers working in Holland at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th shows less of a peculiarly national characteristic than would be the case if such a selection were to be made from, say, the English or German instruments of the same period. Rather, there is an independence which may perhaps equally be viewed as a national characteristic, but which did not result in a consistently identifiable character in the recorders produced by these makers. Instead, the instruments show some individuality, with variety in both tonal quality and compass, and also in the form of the turnery.

As there are elements in the design of a recorder which relate specifically to compass, tonal behaviour, and quality of sound, the variety of form seen in these Dutch recorders provides the possibility of isolating to some extent the causes of their musical individuality.

The physical reasons for the compass and sound quality of a particular recorder type can be found mainly in the profile of the internal bore, and the size, placing, and undercutting of the finger holes. However, the basic dimensions and adjustment of the windway surfaces and labium play a very large part in establishing the final quality of the tone dictated in the first place by the bore of the instrument.

The first instrument, the soprano recorder by E. Terton, has the full Baroque recorder compass of c″ – d″″, together with a firm clear tone. The windway and labium are of normal width, but the sides of the window are much higher than usual due to the very thick walls of this instrument. The increased wall height gives a full and edgy quality to the sound.

The soprano by Richard Haka, while it also has the full compass of the Terton, has a much gentler tone. This is partly due to the lower window sides which result from thinner walls at the block line and a nearly straight labium, but of even greater importance is the smaller than usual jet length (the distance from windway to labium).

The W. Beukers soprano has a narrower compass, c″ – roughly a‴, but has very large voicing dimensions. This gives a strong tone of less subtlety than either the Terton or the Haka, but rather more vigorous in its effect. The Wijne alto, with its very small voicing, has a tone of quite unusual gentleness, but with the full alto compass.

The remaining two instruments, altos by van Heerde and van Aardenberg, also have the limited compass of f' – d‴. However, the fine adjustment of the block/labium relation gives them a full, clear, and responsive sound. The peculiarities of bore which cause the smaller compass also give the second lowest note a very round, firm, and clear tone.

Frederick Morgan

Fred Morgan on Original Baroque Recorders

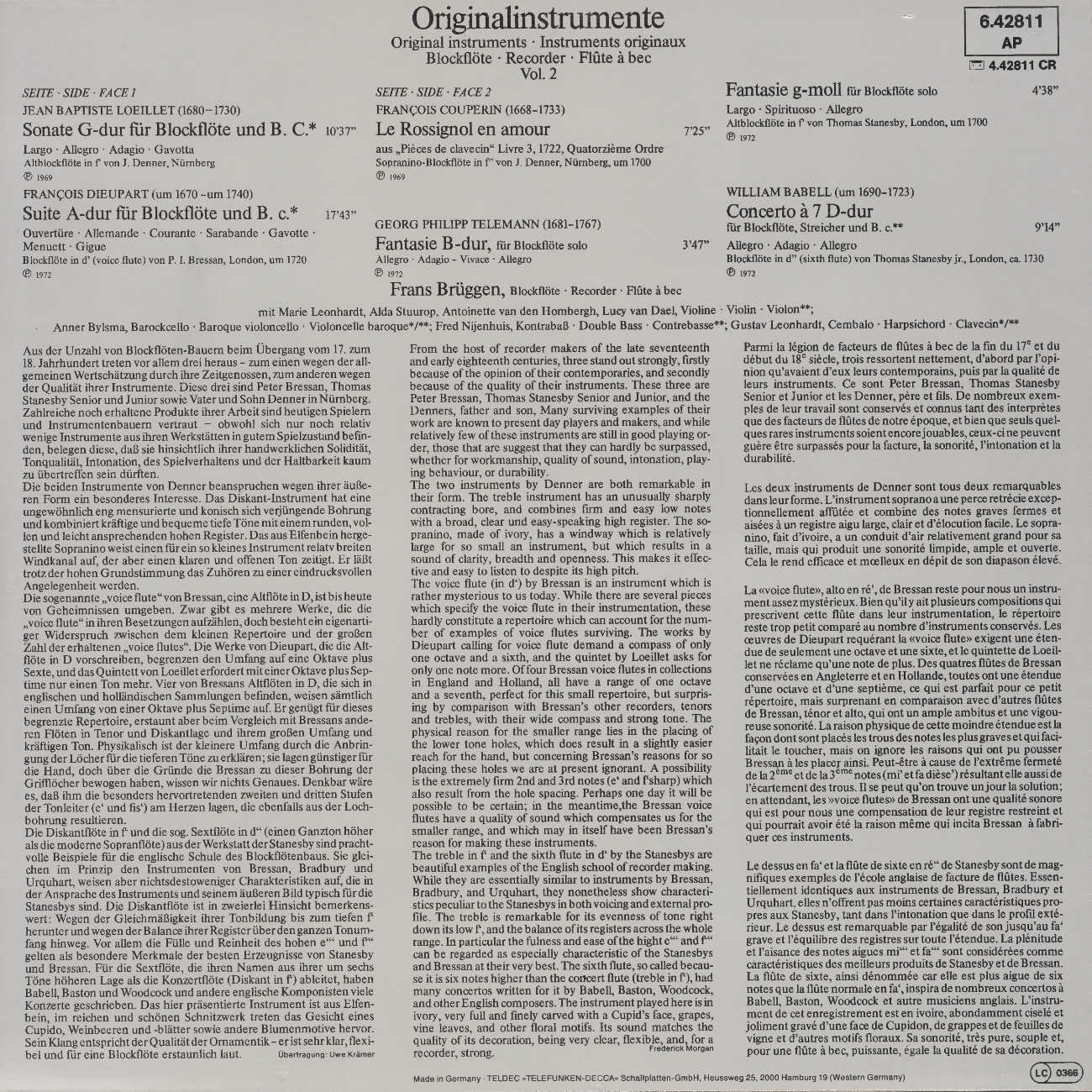

In the liner notes for Vol. 2, Morgan discusses recorders by Bressan, Denner, and Stanesby, featured in the second LP:3

From the host of recorder makers of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, three stand out strongly, firstly because of the opinion of their contemporaries, and secondly because of the quality of their instruments. These three are Peter Bressan, Thomas Stanesby Senior and Junior, and the Denners, father and son, Many surviving examples of their work are known to present day players and makers, and while relatively few of these instruments are still in good playing order, those that are suggest that they can hardly be surpassed, whether for workmanship, quality of sound, intonation, playing behaviour, or durability.

The two instruments by Denner are both remarkable in their form. The treble instrument has an unusually sharply contracting bore, and combines firm and easy low notes with a broad, clear und easy-speaking high register. The sopranino, made of ivory, has a windway which is relatively large for so small an instrument, but which results in a sound of clarity, breadth and openness. This makes it effective and easy to listen to despite its high pitch.

The voice flute (in d') by Bressan is an instrument which is rather mysterious to us today. While there are several pieces which specify the voice flute in their instrumentation, these hardly constitute a repertoire which can account for the number of examples of voice flutes surviving. The works by Dieupart calling for voice flute demand a compass of only one octave and a sixth, and the quintet by Loeillet asks for only one note more. Of four Bressan voice flutes in collections in England and Holland, all have a range of one octave and a seventh, perfect for this small repertoire, but surprising by comparison with Bressan’s other recorders, tenors and trebles, with their wide compass and strong tone. The physical reason for the smaller range lies in the placing of the lower tone holes, which does result in a slightly easier reach for the hand, but concerning Bressan’s reasons for so placing these holes we are at present ignorant. A possibility is the extremely firm 2nd and 3rd notes (e' and f'#) which also result from the hole spacing. Perhaps one day it will be possible to be certain; in the meantime, the Bressan voice flutes have a quality of sound which compensates us for the smaller range, and which may in itself have been Bressan’s reason for making these instruments.

The treble in f' and the sixth flute in d' by the Stanesbys are beautiful examples of the English school of recorder making. While they are essentially similar to instruments by Bressan, Bradbury, and Urquhart, they nonetheless show characteristics peculiar to the Stanesbys in both voicing and external profile. The treble is remarkable for its evenness of tone right down its low f', and the balance of its registers across the whole range. In particular the fulness and ease of the hight e‴ and f‴ can be regarded as especially characteristic of the Stanesbys and Bressan at their very best. The sixth flute, so called because it is six notes higher than the concert flute (treble in f'), had many concertos written for it by Babell, Baston, Woodcock, and other English composers. The instrument played here is in ivory, very full and finely carved with a Cupid’s face, grapes, vine leaves, and other floral motifs. Its sound matches the quality of its decoration, being very clear, flexible, and, for a recorder, strong.

Frederick Morgan

The Internet Archive maintains digital copies of these albums, complete with audio samples and downloadable scans of the LP sleeves. Here are the links for Vol. 1 and Vol. 2.

Unsurprisingly, this project had a significant impact on Brüggen. Here are some impressions from his original 1972 notes:

Playing recorders of the past has been my passion for a long time. To be able now to present a documentation of the sound of the baroque recorder causes me pride, jealousy, modesty, love, anger, anxiety, peace and a good many other feelings at the same time. So much still remains to be learned, to be done, and to be left alone. The spectrum of experiences I have had while working on it is as colorful as one could wish.

However, it is important to note that this type of project poses serious risks to the instruments, as Brüggen acknowledged: “some fine museum pieces have cracked under my hands.” Fortunately, the privately-owned instruments resisted better: “the 8 recorders from private owners, accustomed to being played almost daily by them, refused to crack, notwithstanding even the terrific central heating power at my house.”

At the end of his notes, Brüggen offers a curious prayer:

My God, who is present in the cellars of museums, who can open the eyes of individuals, and knows hidden attics, grant me many more, or all, old recorders.

— Frans Brüggen

As expected, Brüggen’s desire for the original instruments remained insatiable.

-

Frans Brüggen, 17 Blockflöten, Telefunken SMA 25073-T/1-3, Das Alte Werk, 3 × vinyl, LP, Stereo Box Set, Germany 1972. ↩

-

Frans Brüggen, Blockflöte, Recorder, Flûte à Bec - Vol. 1. Telefunken 6.42050 AP, Das Alte Werk, Original Instruments, vinyl, LP, compilation, Germany 1976. ↩

-

Frans Brüggen, Blockflöte, Recorder, Flûte à Bec - Vol. 2. Telefunken – 6.42811 AP, Das Alte Werk, Original Instruments, vinyl, LP, compilation, Germany 1976. ↩